Foundry West Shore (Coming Soon)

Contact

Land Acknowledgement

We acknowledge with gratitude that Foundry West Shore will operate on the traditional and unceded territories of the Coast Salish Peoples, including the Nations of Esquimalt (Xwsepsum/Kosapsum), Songhees, T’Sou-ke, Sc’ianew (Beecher Bay), and NuuChahNulth Peoples of Pacheedaht. We honour and respect Metis, Inuit, First Nations, and commit to fostering culturally safe and inclusive spaces for all youth and families and to building meaningful, ongoing relationships with the Nations whose lands we are privileged to share. We commit to reconciliation, decolonizing our health care practices, and Indigenous youth-led health solutions that support current and future generations.

Foundry West Shore will support the health and wellness needs of youth and their families in the West Shore area including Langford, Colwood, Metchosin, The Highlands, Sooke, and Port Renfrew. Our services will be free and confidential.

Foundry West Shore will be hosted by Thrive Social Services Society. At Foundry centres, multiple service providers and organizations work together to provide a variety of services to youth ages 12-24 and their families.

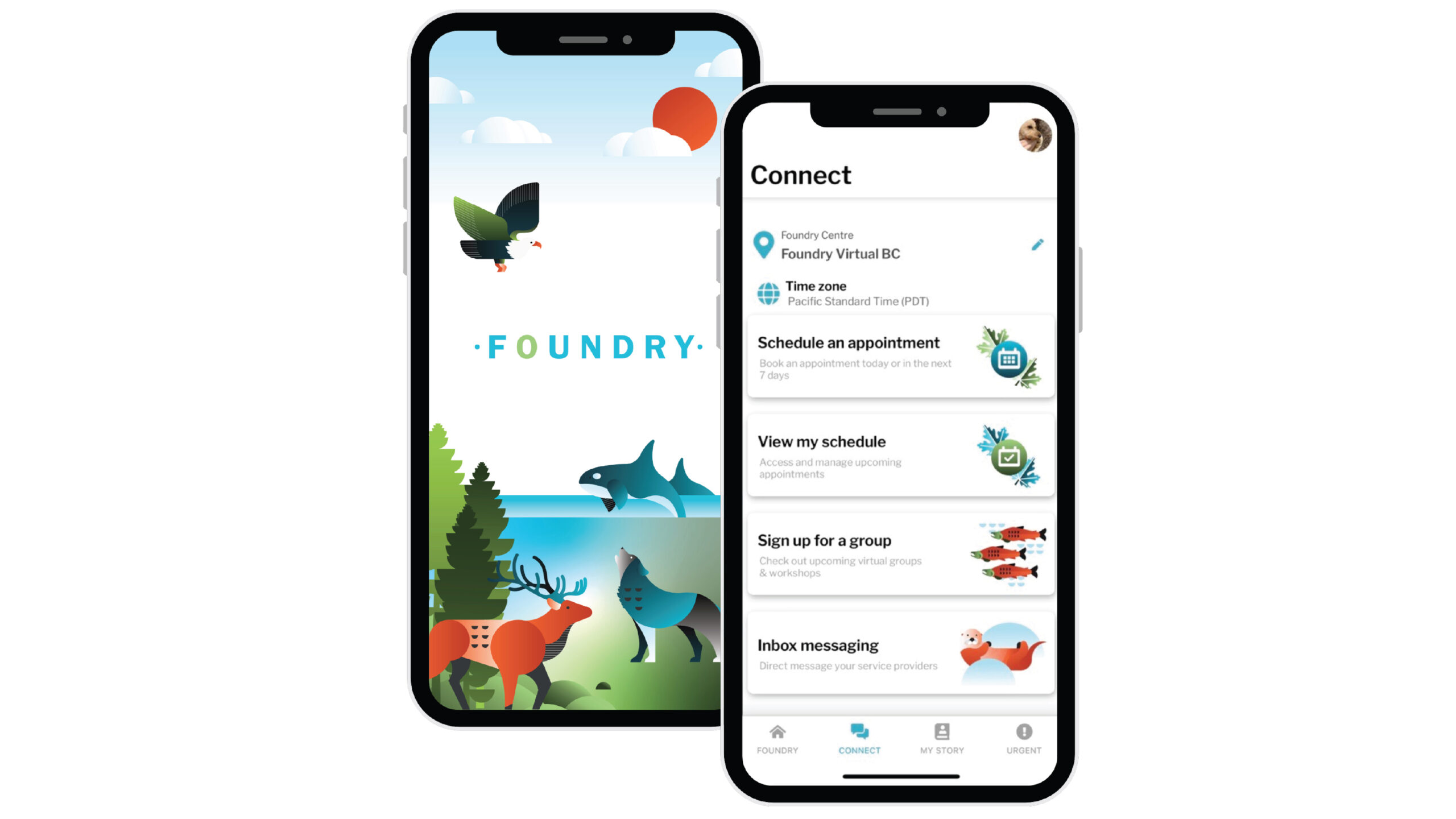

Foundry West Shore is part of Foundry’s network of centres across BC. Want to learn more?

Get Involved

If you are a young person or supporting a young person, you can find out more by dropping by to see us at an upcoming community event, reaching out to us via email, or subscribing to our newsletter to receive regular updates about the Foundry centre coming to serve the West Shore and Sooke communities.

Got a question? Please get in touch, because we’d love to hear from you. Drop us a note!

Careers

Foundry West Shore does not have any job postings to share at this time. Check back here later for future opportunities.

Donate

Make a difference for youth in the West Shore, Sooke, and Port Renfrew by donating to Foundry today. Your support helps create welcoming spaces and accessible services for young people.